(Originally published on Explicit Gamer, a videogame website that vanished into the ether overnight)

We have been blessed with a console generation that seems to extend to infinity. Sony won’t utter a whisper of the mere possibility of a next machine; Microsoft prepares to roll out its motion-based Natal functionality for the 360; Nintendo counts the billions earned from the Wii and DS which don’t have to be sunk into research and development. Nevertheless this current cycle will end, and if you listen closely, you can hear the buzzwords of the future: 3D, voice recognition, digital distribution, cloud computing. What you can’t hear, what these company’s representatives won’t dare let slip, is one from the past: backwards compatibility. Indeed, there is a frightening possibility that these technological marvels residing on the digital horizon will not play the games which you and I currently own.

This possibility becomes a probability when you consider how little regard gaming bigwigs hold for those gamers who do play older games on their spiffy new consoles. “Nobody is concerned anymore about backwards compatibility,” former Xbox VP Peter Moore once famously declared before adding, “we under-promised and over-delivered on that.” On this issue he finally had some common ground with his rivals at Sony, such as Director of Marketing John Koller who whipped out the charts and graphs before concluding, “Most consumers that are purchasing the PS3 cite PS3 games as the primary reason.”

Elaborate justifications fueled by research and focus testing are not necessary. Anyone who spends several hundred dollars on a video game console is obviously going to gravitate toward the games and features that “show off” this expensive new gadget. What Moore and Koller fail to grasp is the same fact that market leader Nintendo has completely embraced: classic video games are the legacy of the medium. By denying gamers easy access to prior generations’ games, executives are cutting off gaming at the knees.

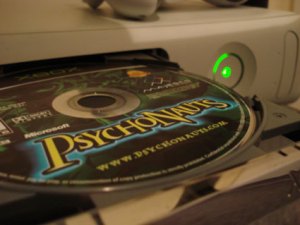

Film and music lovers have a huge catalog of titles, collectively spanning centuries, from which to draw. We gamers don’t have this. Our catalog primarily consists of whatever games were released in the current generation, plus the ones that the console manufactures have seen fit to toss back out there and charge money for. The idea that a system called the PlayStation 3 does not play all games bearing the PlayStation banner is ludicrous. The fact that Oddworld: Stranger’s Wrath, an acclaimed game that debuted five years ago on the original Xbox, is completely unplayable on the Xbox 360 is ludicrous. The certainty that the only way to play these incompatible games is on the systems they were originally released for is, likewise, ludicrous. Do Blu-ray fans keep a DVD player nearby for watching old DVDs? Of course not. Movie execs understand that new technology should render old hardware obsolete, while video game execs are content to see the software fall into oblivion. The gaming overlords need to be reminded that consoles are only as strong as the games we play on them. Without software — new and old — this business is dead in the water.

Film and music lovers have a huge catalog of titles, collectively spanning centuries, from which to draw. We gamers don’t have this. Our catalog primarily consists of whatever games were released in the current generation, plus the ones that the console manufactures have seen fit to toss back out there and charge money for. The idea that a system called the PlayStation 3 does not play all games bearing the PlayStation banner is ludicrous. The fact that Oddworld: Stranger’s Wrath, an acclaimed game that debuted five years ago on the original Xbox, is completely unplayable on the Xbox 360 is ludicrous. The certainty that the only way to play these incompatible games is on the systems they were originally released for is, likewise, ludicrous. Do Blu-ray fans keep a DVD player nearby for watching old DVDs? Of course not. Movie execs understand that new technology should render old hardware obsolete, while video game execs are content to see the software fall into oblivion. The gaming overlords need to be reminded that consoles are only as strong as the games we play on them. Without software — new and old — this business is dead in the water.

In the age of optical media, lack of backwards compatibility is indefensible. Microsoft certainly had its reasons for going with limited emulation-based BC for the Xbox 360, as did Sony for stripping newer PS3s (and all European ones) of the function. However, these reasons boil down to one thing: money, and the reluctance to spend it. Moving forward, financial excuses just don’t cut it anymore. These companies need to provide full BC in their next consoles on Day One, or they fail. It is their duty — to the consumer and video gaming as a whole. It’s time to start building a catalog of games which pushes forward while honoring the past. It’s time to stop hitting the reset button.